With cinemas closed, Ghana’s hand-painted movie posters find homes abroad

With a swift stroke of his paintbrush, Ghanaian artist Daniel Anum Jasper equipped actor Paul Newman with a pair of revolvers in his bustling studio in Accra. Unfinished paintings featuring a bell-bottomed John Travolta and nunchuck-spinning Bruce Lee adorned the studio walls, showcasing Jasper’s skill as a veteran movie poster designer.

Jasper, renowned for his work on hand-painted movie posters, was in the final stages of completing a commission for the 1969 classic “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.” The request had come from a foreign collector who reached out via Instagram. Between the late 1970s and the 1990s, Ghana nurtured a tradition of advertising films through vibrant hand-painted posters. During this period, local cinemas thrived, and artists vied to attract audiences with their often vivid, imaginative, and striking displays.

As a pioneer of this tradition, Jasper has been crafting movie posters on repurposed flour sacks for three decades. However, the dynamics of the market have shifted. Jasper noted, “People are no longer interested in going out to watch a movie when it can be watched from the comfort of their phones.” Despite this change, there is a growing international interest in owning these hand-painted posters. Collectors now showcase them in private spaces or exhibitions.

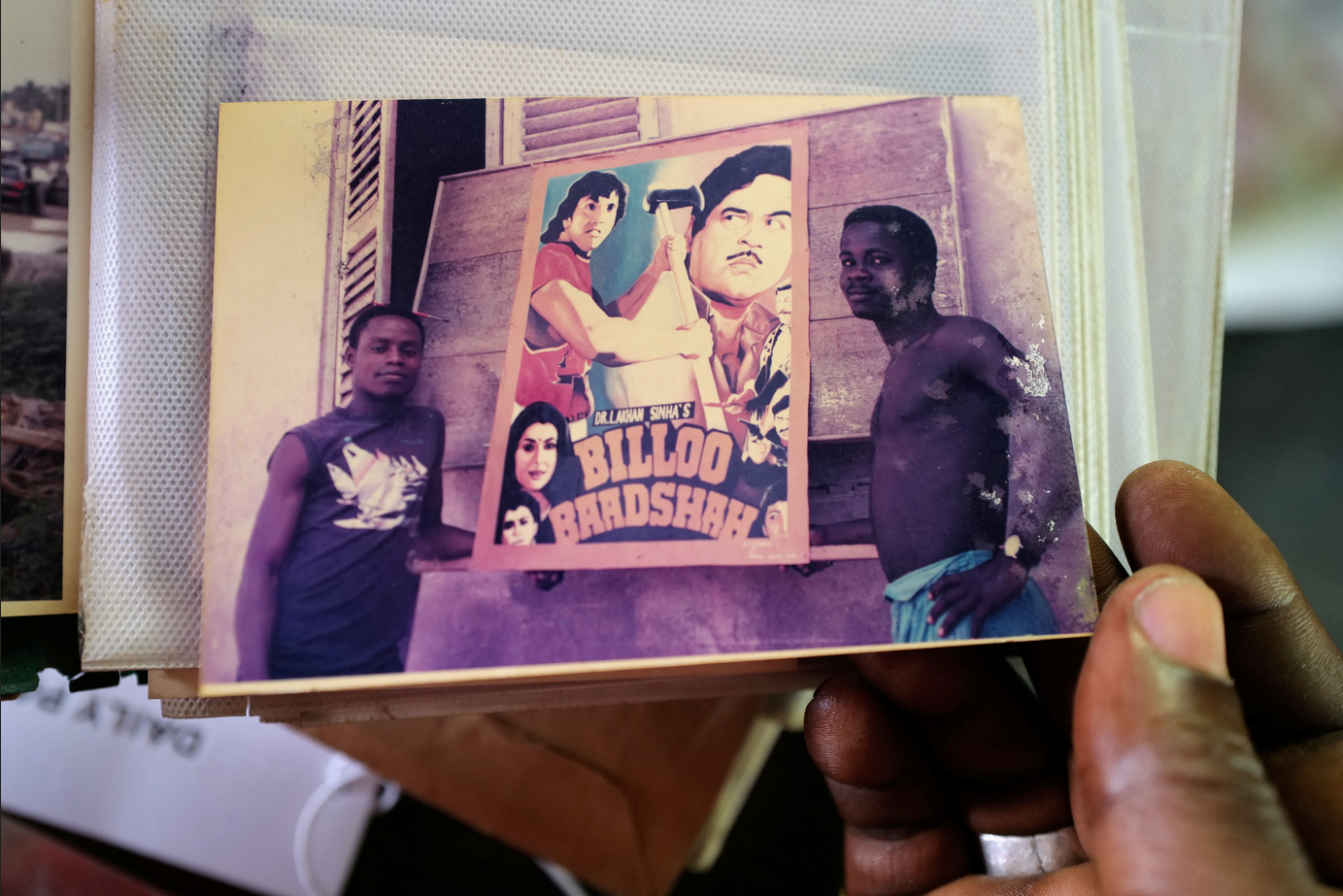

The internet’s ascent led to the decline of Ghana’s independent cinemas. Nevertheless, Jasper’s work has found appreciation abroad, particularly in the United States, where these posters are cherished as unique representations of a specific era in African art. The tradition predominantly featured Western action films, Bollywood productions, and Chinese pictures. Many posters incorporated paranormal elements and exaggerated violence, even if the films themselves lacked such content.

Joseph Oduro-Frimpong, a professor of pop culture anthropology at Ashesi University in Ghana, is an avid collector of Jasper’s paintings. Having amassed these posters over the years, he plans to exhibit them at the Centre for African Popular Culture at the university later in the year. Oduro-Frimpong emphasized the historical significance of these posters and their potential to spark conversations, stating, “We tell them not to think about what they’re seeing now… (but) to think of these art forms as symbols of history that can tell their own stories.”